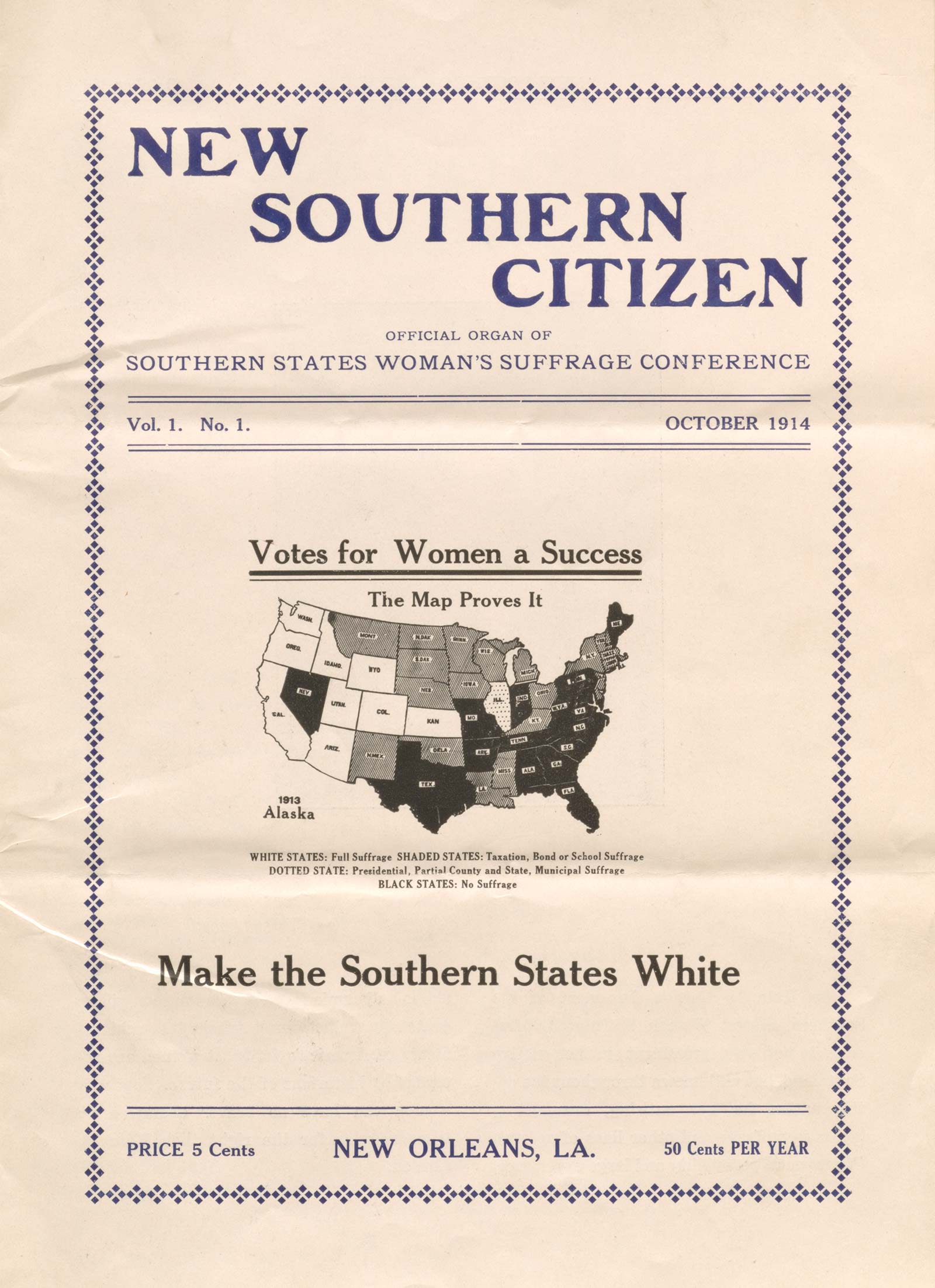

“Make the Southern States White”

Racism and the suffrage movement went hand in hand. During the debate over the adoption of the Reconstruction amendments in the 1860s, Elizabeth Cady Stanton egregiously questioned why the rights of newly freed African American men took priority over (to her mind) more qualified and deserving white women. A widely circulated 1893 print by Henrietta Briggs-Wall called “American Woman and Her Political Peers” showed temperance activist Frances Willard surrounded by likenesses of an idiot, a convict, a Native American, and an insane man. The suffrage movement itself effectively shunted African American women into their own separate organizations. And when NAWSA met in Atlanta in 1895, black women were not allowed to speak.

Southern suffrage was always very much tied up with race. Even after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, Southerners feared the federal government might enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments more aggressively. That fear provided an opening wedge, albeit a racist one, for the suffrage movement to take root in the 1890s: enfranchising white women, it argued, would offset votes by black men. By the turn of the century, black men had been effectively disfranchised, so there was less need to portray woman suffrage as a cornerstone of white supremacy. But states-rights Southerners still recoiled at the prospect of yet another federal amendment on what they saw as a state and local matter. Organizations such as the Southern States Woman’s Suffrage Conference, led by Kate Gordon of Louisiana, once again played the race card to “Make the Southern States White.” In the end only four Southern states (Texas, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee) voted to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.